Amidst a language immersion program the fall of my senior year in Dijon, France, I found myself wondering into the Musée d’Art et d’Histoire du Judaïsme, located in Le Marais, a neighborhood I found myself returning to over and over. My first visit with C, then with my mom, and back again several times throughout my semester. I knew which coffee shop was open before ten and where my favorite window shopping stores were located. It’s winding narrow roads became familiar, soothing.

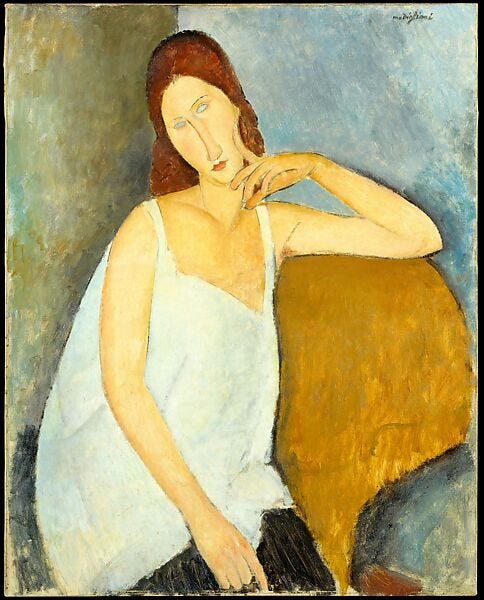

With a month till its closing, the Chagall, Modigliani, Soutine… Paris as a School, 1905-1940 exhibition compelled me inside, Modigliani’s evocative portraits a reminder of the art course I took my very first semester of college in Copenhagen. Fleeing persecution in European cities and pogroms in the Russian Empire, these Jewish artists in search of artistic, social, and religious emancipation found together within a community.

“The gorgeous cacophony of humanity […] It’s impossible to describe. But it all boils down to the same thing. Love.”

I recently finished The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store by James McBride. It lived at the top of my to-read list, it’s plot line and apparent themes pulling me in. Plus, it was on Obama’s Favorite Books of 2023 list (so I could almost guarantee it would be good).

It’s a compelling novel that begins in 1972 with the discovery of human remains in a well, prompting a murder investigation in the town of Pottstown, Pennsylvania. The only clues—a belt buckle, a pendant, and a mezuza—lead the police to consider the last remaining Jewish man in town as a suspect. End scene.

The story then rewinds to the 1920s and ’30s, to Chicken Hill, the neighborhood in Pottstown where Jewish, Black, and immigrant communities live together, ultimately linked by love and duty.

The ever-present themes woven throughout this novel took me back to my visit to the museum. I also read it with the foundation of knowledge I gained from a Jewish American Literature course and an Ellison & Melville Literature course. It was in the former that I truly felt like a writer for the first time, despite it being an academic lens. The course and professor valued the innovation of ideas and this freedom availed me in reading a text and feeling like I had something unique to say—and the ability to express it poignantly.

“Rather, she saw it as a place where every act of living was a chance for tikkun olam, to improve the world. The tiny woman with the bad foot was all soul. Big.”

The book is full of powerful and distinct characters. Mosche and Chona Ludlow, a Jewish couple, own The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store. The grocery store doesn’t generate much income because Chona, known for her kind soul, allows the community to buy groceries on credit without expecting repayment. The store is mainly Chona’s endeavor, while Mosche runs the local theater, achieving financial success, defying societal norms, and bringing people together through entertainment.

“This is old thinking in a new time, and I must change.”

Malachi, the dancing man who comes and goes, whispering words of wisdom when he appears when least expected is the character who repeatedly insists that Mosche must embrace new endlessly in order to sustain success. Walter Benjamin’s concept of the Angel of History presents an intriguing perspective: while humans perceive history as a sequence of catastrophes, the angel sees all of history as one continuous catastrophe. We often believe we are making progress, but the angel wants to awaken us to the ways in which we are entrenched in ongoing disasters. Who provides the angelic vision in this story? Malachi.

“There was a silent pool in Nate Timblin, a stirring that did not invite foolishness, a quiet that covered a kind of tempest.”

Feared and respected by the Black community for reasons that slowly unfold, page by page, Nate Timblin works for Mosche at the theater, and he’s married to Addie, Chona’s friend. Intertwined, deeply, with various characters and communities allows him to successfully play the role he does in the end.

The truth was, the only country Nate knew or cared about, besides Addie, was the thin, deaf twelve-year-old boy who at the moment either was riding a freight train to Philadelphia or was a full-blown ghost wearing a schoolboy cap, old boots, and a ragged shirt and vest, standing ten feet from him and tossing small boulders into the Manatawny Creek before his eyes. Which one was it? “Dodo.”

And then, there’s Dodo with which a key conflict arises. He is a deaf, orphaned child who becomes a pivotal character through which the various communities of Chicken Hill unite to protect. When a series of injustices threaten Dodo and the health of Chona, the residents band together.

The murder mystery gradually unfolds as the story bridges past and present, revealing many truths (some of which only the reader is privy to). At the same time, it exposes the appalling role played by the town's white establishment.

McBride powerfully challenges notions of alienation amongst marginalized communities through the narrative. Despite existing on the fringes of 20th century America together, it is the tensions (the earthquake kind) that yield a new way of being in the world for Chicken Hills’ residents. One united in a nation that fails to uphold its values of freedom and equality.

“…for in death, Chona had smelled not a hot dog but the future, a future in which devices that fit in one’s pocket and went zip, zap, and zilch delivered a danger far more seductive and powerful than any hot dog, a device that children of the future would clamor for and become addicted to, a device that fed them their oppression disguised as free thought.”

In class, I wrote an essay on how the women in Tony Kushner’s play Angels in America serve as vessels through which culture and its ideas, beliefs, and understandings can be pioneered. Similarly, at this point in the novel (see quote), Chona enters into an imaginary sphere that anticipates the modern day struggle against technology. The frantic nature of the sentence, and the thought, and the diction is reminiscent of the fantastical nature of the play. Through Chona’s character, McBride can eloquently critique today’s society without preaching and risking it’s dismissal. Brilliant!

“Light is only possible through dialogue between cultures, not through rejection of one or the other.”

The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store captivates with its magical characters, poetic prose, and profound narrative. McBride's storytelling evokes deep contemplation and warrants enduring engagement, leaving me eager for discussion. Drawing inspiration from the brilliance of past writers and thinkers, McBride crafts a poignant narrative that lingers in the mind long after the final page.